Article, Photos & Video by Lyn Burks

Rotorcraft Pro Media Network

Helicopter flight training wearing Night Vision Goggles (NVG) is as exciting and interesting as any other new skill or technique that can be learned in a helicopter. It’s right up there with learning touchdown autorotations! The one and only buzzkill is that, as the name of the device suggests, you must be using them at night. It’s all fun and games — until your flight-training block is from 0200 – 0400.

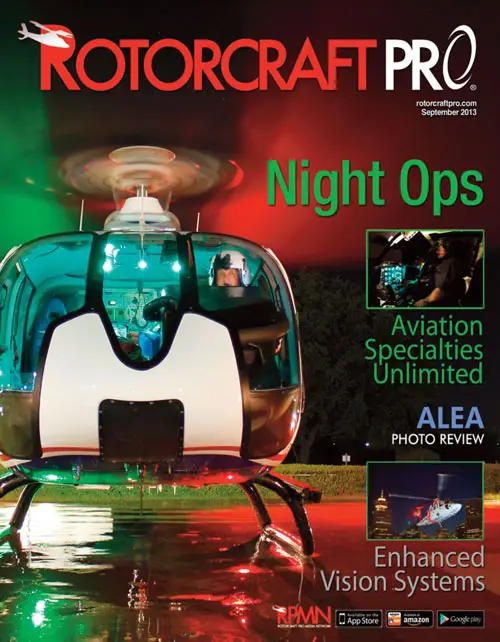

All whining aside, it’s 0145 and Aviation Specialties Unlimited (ASU), Director of Ops and Lead NVG Instructor Pilot, Kim Harris, is briefing me on our upcoming training flight. I am sitting in a very modern training room in front of a 60” HDTV connected to the Internet. I’m first briefed on the training flight itself, as we cover some of the techniques and maneuvers we will be working on.

Next, for the sake of situational awareness, Kim pulls up on the HDTV, a VFR aeronautical chart and Google Earth so that we can look at the surrounding airspace and terrain in which we will be training. Additionally, we look at lunar tables, weather (METAR & TAF), and NOTAMs for the area. The last thing we do before strapping into ASU’s Bell 206 Jetranger for the training flight is to grab the L-3 NVGs from the locker and go through a complete inspection procedure.

From initial brief, to flying the helicopter, to pushing the helicopter back into the hangar at the wee hour of 0400, I learned several new skills. I also had the chance to polish some rusty skills that had not been used in a while. My training session with Kim, although educational, was only one learning objective of many during my visit to ASU’s headquarters, which are nestled in the beautiful high desert town of Boise, Idaho.

As you will see, this 18-year-old company has learned many lessons from the school of hard-knocks. It has also pioneered and clawed its way up to become a leader in the NVG industry.

Slow Start

ASU’s humble beginnings started in 1995, when Mike Atwood had a vision of bringing NVGs, historically reserved for military operations, to the masses in the civilian helicopter industry. Since 1978, Mike had been actively involved in Night Vision Programs in military, government, and civil flight operations, so his background gave him the knowledge base he needed to strike out on his own. He recognized, before it was hip to say so, that NVGs would be the key to safer night helicopter ops in sectors like EMS and Law Enforcement. As are most good ideas, his vision may have been born before its time. Fortunately, time would be on his side.

Armed with past experience using NVG technology, thousands of helicopter flying hours, and a Helicopter Airline Transport Pilot Certificate, Mike Atwood started ASU from a home office in 1995. He then hired Hannah Gordon (now Director of Sales and Marketing) as the company’s first employee. Being an EMS pilot myself at the time, my personal recollection is that from the period of 1995 to 2001, NVGs were really an enigma to the civilian world. There seemed to be lots of pontification among the operators, pilots and regulators about how to use NVGs, but few were out there championing their use at the time. Newly formed ASU had the vision, but without demand, a willing industry, and a cooperative regulatory body (FAA), the first-half decade of the upstart would be like “pushing a rope uphill,” according to Hannah Gordon.

Growth & Hard Knocks

It was not until January 29, 1999 that the FAA issued the first Supplemental Type Certificate (STC) to permit use of night vision goggles by a civilian Helicopter Emergency Medical Service (HEMS) operator. This event sparked a national conversation within the helicopter industry that rumbled just below the surface for a few years. Additionally, there were two other narratives playing out that would set the stage for explosive growth for NVG integration into the helicopter industry.

First, there was an unacceptably high fatal accident rate in the helicopter EMS sector that kept the FAA shining light of scrutiny upon it. This attention by the FAA was creating a sense of urgency by HEMS operators and industry groups like AAMS, NEMPSA, and HAI, to find solutions to the accident problem. Second, due in part to favorable legislation surrounding HEMS flight reimbursement, the business of HEMS was booming and new HEMS bases were growing at a double-digit pace year after year.

In 2003, it seemed the pendulum finally swung in the other direction as the civil helicopter industry embraced NVGs as a legitimate tool for improving safety in helicopter night operations. A new industry was born, and NVG proliferation into sectors like Law Enforcement and HEMS exploded.

Fortunately for ASU, with its expertise and specialized skill set, it was positioned perfectly to capitalize on this growth. In order to keep up with work demand, ASU went from being a very small company with a two-person staff in 2002, to over 20 employees in 2007. They went from a home office, to a legitimate 10 x 20 office, to their current offices / hangar in short order. Naturally, this growth, as is always the case, did not come without growing pains.

There was no shortage of operators wanting to integrate NVGs into their aircraft and operations, and ASU worked hard to provide services to as many clients as they could manage. At the time, the real speed bump in the road was that the regulatory body governing NVG technology integration, the FAA, was not keeping pace with an industry on the move.

Looking back, it was not entirely the FAA’s fault. Since there was not much of an experience base within the FAA, they were slow to move because few people in the ranks really understood the civil helicopter industry and how NVGs fit into it. This resulted in very inconsistent handling of helicopter operators by FAA Flight Standard District Offices across the nation. As an example, an aircraft / program owned by ABC Company could seamlessly integrate NVGs at bases in the northwestern US, while the same exact operator / aircraft / program would be treated differently in the southeast US. In the early days, a confusing, inconsistent, and evolving regulatory framework would prove to be ASU’s greatest challenge during its initial growth spurt.

Pushing The Rope Uphill

As time passed, both the FAA and ASU got better at what they do. Both, in addition to other players in the NVG market, recognized that education and cooperation was key to the goal of getting this technology safely into the helicopters needing it. To their credit, they all proactively pushed the rope uphill. ASU sponsors, and participates in, steering committees and educational opportunities like the Night Vision Advisory Council (NVAC), the Night Vision Awards, as well as the two-day NVIS Conference, NightCon. In turn, the FAA attends NightCon each year to listen to, and interact with, NVIS operators and service providers.

According to Mike Atwood, ASU’s patriarch, “As an industry we still have room for improvement, but we are not all moving in total opposite directions, as in the early days. We all have a common goal, and that is to use this technology and expertise to make the industry safer — and that is a noble reason to work together.”

Eighteen-years after its start, ASU now provides any operator wanting to integrate NVGs into its operation, a one-stop-shop-service for doing so. They provide their customers NVG equipment, cockpit modifications, maintenance, parts, service, and training. They also manufacture many of their own parts. In 2003, ASU brought the task of cockpit modifications in-house and began manufacturing all of its own parts through its Parts Manufacturing Authority (PMA). Although this required significant investment in time and dollars, it allowed them to control quality, have a really fast lead time, and high field serviceability for their customers.

Pilot training is a staple of ASU’s business, and a natural by-product of its business model. Having said that, ASU made it very clear to me that they do not just train pilots to fly using NVGs. From a pilot training perspective, Kim Harris characterizes the company as being more of a solution provider.

When asked to explain, he indicates that teaching a pilot to fly using NVGs is not all that difficult. The real challenge is going into an operation (civilian, paramilitary, or military), take their tasks normally reserved for daytime operations, and then teach them how to safely do those same tasks under the cover of darkness.

Since ASU has a cadre of instructors with extensive military and civilian helicopter experience, ASU has trained foreign military and paramilitary operators to perform tasks under NVGs, such as aerial gunnery, fast-roping, sniping, formation flying, and SAR operations. “Turning a customer’s complex daytime task into a ‘routine’ nighttime operation is a testament to ASU’s commitment to be a total training solution provider,” says Harris.

Looking To Future Growth

According to Gordon, ASU now holds 23 STCs on over 60 makes / models of aircraft. Additionally, ASU has clients in 50 countries, on six different continents, and has completed over 700 commercial aircraft installations.

It has taken nearly two decades to build a business in a small niche industry. Looking to the future, ASU wants to continue to control growth and expand into new markets. As part of that expansion, ASU recently committed to double the size of their current 12,000 sq. ft. hangar and office facility. Gordon indicates that although domestic NVG markets will still be a staple for ASU, the real growth for them, and NVG proliferation, will be in international markets. Given its pioneering past and ability to overcome and adapt to rapidly changing business environments, I am confident that ASU will continue to contribute to a safer helicopter industry for years to come.